Some thoughts on the differences between the French and US reactions to the Covid-19 pandemic from a native Frenchman and proud US citizen.

We moved to Palo Alto in 1989, a few weeks before the Loma Prieta earthquake. In retrospect, it was a minor disturbance compared to today’s challenges. Four times a year we fly to Paris to spend time with family and friends, sinning with controlled abandon. No more.

This gives rise to a somber meditation on the way the two cultures have handled the Covid-19 crisis. We’ll start with an obvious difference: healthcare.

France and the US were both equally ill-prepared, poorly stocked in the basic tools to combat the exponential rise of virus contamination, but beyond that, the two countries diverge. To put it summarily but not unfairly, in the US you can go bankrupt because you have cancer, you can lose insurance coverage if you lose your job, and so on. No such threat in most Western Europe countries.

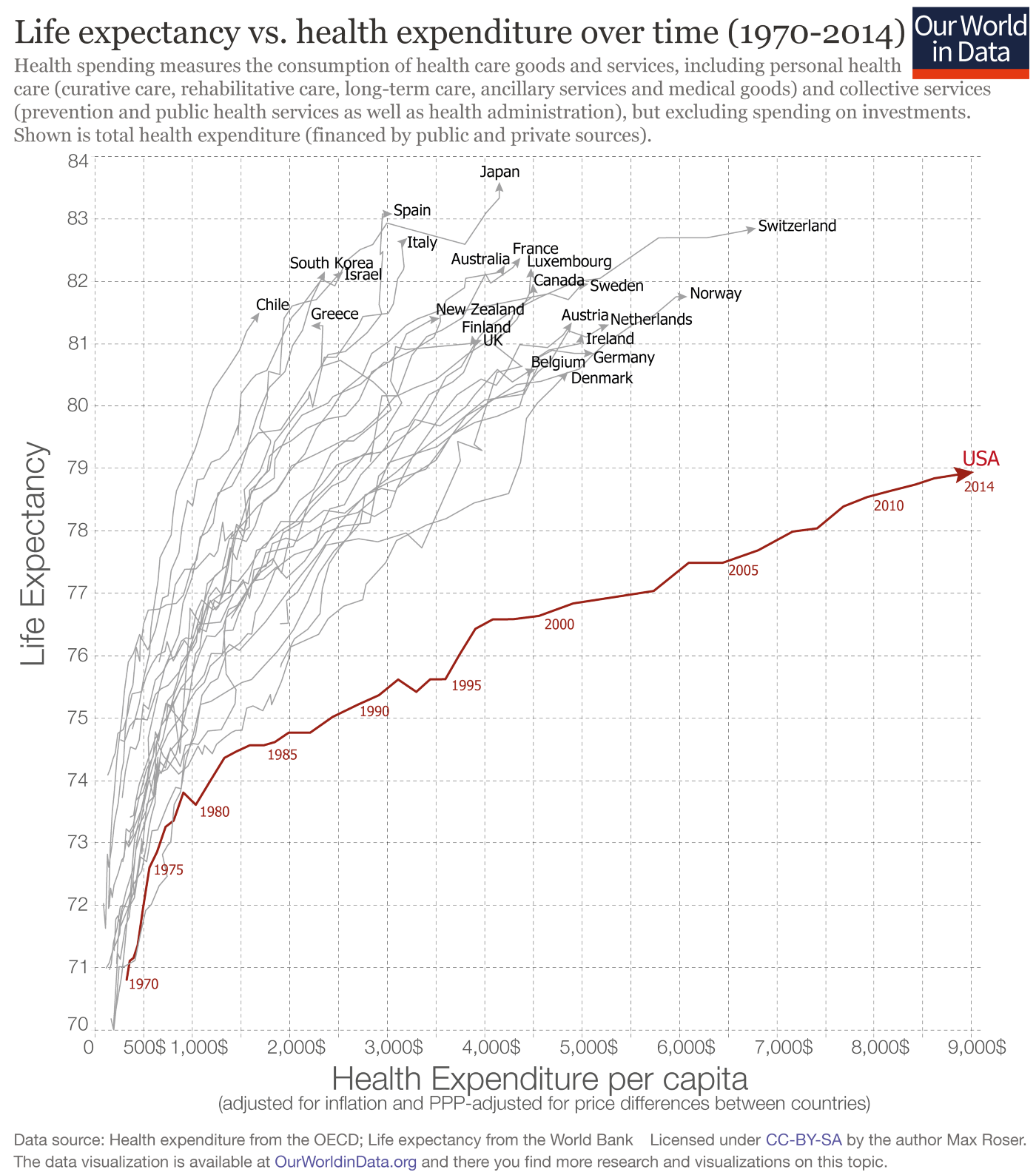

In a March 2017 Monday Note titled The Hopeless Health Care Rip-Off, I published this ourworldindata.org chart:

As one of my Be colleagues used to say: US healthcare costs more but it does less.

In the US, we spend trillions upon trillions in bailouts and losing Middle East wars, but we don’t seem to have the dollars — or guts — to dismantle the political structure that makes the healthcare regulation war unwinnable. The unshakable relationship between politics, insurance, hospital and drug companies has made the price of medicines and health services in the US inviolate. France, and most other Western democracies, see healthcare as a human right, not a profit center.

Let’s move to confinement at home.

The latest California decree lets me take long walks for my health and go shopping for groceries. I appreciate the freedom, although at my age (76) and burdened by a hematological problem, my wife and I opt for home delivery instead of retail therapy, and enjoy long video conferences with family and friends.

In France, after a sequence of progressively tighter restrictions, you now must carry a certificate that justifies your need to leave your domicile. You can go to work, or to the doctor or supermarket, but jogging and cycling expeditions are verboten beyond one kilometer — 2/3 of a mile — from your home, and only one person at a time. The police are everywhere and the fines are heavy: $150 for the first infraction, escalating rapidly, ending with prison sentences for repeat offenders.

On the bright side, Europeans open their windows at 8pm to applaud and sing homage to the doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers on the front lines combating the pandemic (from Time magazine):

“They stand at open windows or on balconies in Rome, Madrid, Paris, Athens and Amsterdam, singing, cheering and applauding even though they know their intended audience is too busy to listen. The adulation is for the doctors, nurses and other health care workers putting themselves at risk on the front lines of the pandemic that is forcing most residents to stay home.”

In both nations we see signs of rebellion — or boredom. Here, we had a boisterous and defiant display of crowded Florida beaches during Spring Break, a scene that admits a dark, almost funereal thought as we imagine the revelers returning to their colleges at the country’s four corners, likely spreading the virus.

In the poor areas of Paris and other big European cities, where the black market economy is the only way to make ends meet, people are showing signs of restlessness and, a readiness to revolt against authorities. Although the police have been instructed to employ a “discerning attitude” towards the sale of contraband, customers’ freedom of movement is so severely curtailed that there’s no commerce to ignore. Some French government officials foolishly applaud the situation as a new found sobriety; the more experienced ministers understand that the last thing France needs is social unrest as it deals with shortages in hospital beds, respirators, masks, and test kits.

(Anecdotally, my friends in France profess incredulity when they learn that San Francisco’s mayor London Breed has finally deemed cannabis dispensaries “essential activities” and can stay open even as bars must remain closed. I point out that while their Gallic sense of proportion and justice is commendable, it’s too bad that they risk jail for their weekend CBD or THC relaxations.)

We now must turn to a serious topic of both ethical and political importance: When to reopen the economy. According to worldometers.com, France has more than 37K cases and 2.3K deaths, and the numbers double every three or four days. The US has 123K cases — the most for any country — and 2.2K deaths. With these growing numbers, how does one balance confinement, which clearly saves lives, versus restarting the economy in order to save livelihoods?

The thought in the US, at least as exemplified by the President, is that we mustn’t kill the economy in the uncertain hope of saving a few lives. We should forge ahead and reboot the country back into business in short order — say two weeks from now, on a beautiful Easter Sunday.

In Europe, the inclination is to keep saving lives, economic costs be damned. The devastation in Italy, Spain, and now in France has led Prime Minister Édouard Philippe to concede that the worst is yet to come, that France needs to maintain its current confinement measures for another two weeks and probably more.

The US and French governments have at their disposal some of the best actuaries and economists, people who can perform sophisticated cost-benefit analyses of a number of scenarios. Another week of lockdown will cost X jobs and require Y dollars (or euros) but will save Z lives.

Thinking in absolutist terms, one couldn’t take the wheel because of a possible deadly accident a few miles from home. In deciding to drive our vehicles, we make a probabilistic cost-benefit analysis. We decide that the cost of driving, the possibility, the cost of getting killed, is vastly outweighed by the benefit of getting to work or to the beach.

The problem with applying economic impact versus lives saved to this situation is that we’re dealing with non-linear phenomena. With the exponential growth curves we’ve observed in contaminations and deaths, a small variance in initial estimates yields large uncertainties as weeks or months are forecast. We don’t know enough about this virus, about silent propagation by asymptomatic carriers to be certain of our assumptions. We don’t know enough but decision time comes and a scenario must be picked. This is when other factors weigh in.

In France, there is no presidential election for another two years. In the US we’re voting next November and the state of the economy will weigh heavily on the result.

Two apparently simple scenarios then emerge.

France’s lesser electoral pressure allows it to pick a more humanistic scenario, keeping the economy locked down a little longer in order to save more lives. In the US, the White House team believes rebooting the economy as soon as possible will keep the current resident in office for another four years — at the possible cost of the thousand of lives that would have been saved had the lockdown stayed in force for another month or two.

But there’s a problem with the apparent simplicity: we don’t really know.

We don’t really know how long the French will tolerate the very strict lockdown before another wave, stronger this time than last year’s Yellow Vests, succeeds in toppling the Macron presidency.

We don’t know, in these non-linear times, how soon and how well the US economy would reboot, and we don’t know how many more thousands of people would die in the meantime and how strong the public revulsion would be.

Non-linear times indeed.